Rick Liu

Cannon Editor-In-Chief

On November 10th, The Varsity published an article titled “Participation in student government elections at UofT among lowest in Canada”. While most students know voter turnout for student elections is low, what is surprising, at least to me, is that the author found that turnout for UTSU elections is abnormally low compared to other schools. Most schools in that article had a student turnout of around 20% compared to the 4% of the last UTSU election. UBC, which is a similar institution to UofT with its large commuter and international student cohort, had a turnout of 24%, so low turnout cannot solely be caused by UofT’s large student body, international students, or large numbers of commuters.

This article pushed us to do an analysis of student turnout at a more local level. I decided to compile the turnout for all class representatives, Officers, Discipline Club Chairs, and Board of Directors elections from the previous election cycle. This would include the March, April, September, and November 2019 elections. I excluded elections for positions such as Common Room Manager, or Social Director, and other discipline club positions, because I did not or could not find the associated rules in the discipline club constitutions for who is eligible to vote or run for those elections in all disciplines. In addition, not all disciplines have the same set of elected positions; many don’t have an elected common room manager for example, so it would be unfair to include those positions for comparisons. I also excluded levy referenda, since turnout to those are more driven by “get out the vote” efforts by design teams.

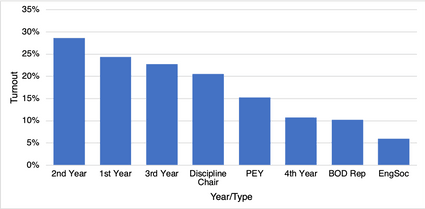

What I found is not surprising. At 18%, EngSoc elections have a higher turnout than UTSU elections, but turnout is still very low, and many races are uncontested, meaning there’s only one candidate running to be a representative. Acclamation is a huge concern, because having only one candidate depresses turnout. Participation in these elections is still important, because the student body still has a chance to be able to reject the candidate. On average, I saw races with one candidate running have an average turnout of 14%, compared to an average turnout of 24% with two or more candidates running.

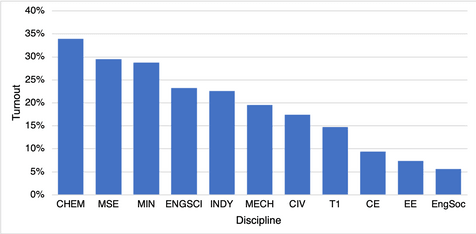

Turnout isn’t the same across all the disciplines, years or elections. I found that Chemical Engineering had by far the highest turnout. At an average turnout of 34%, 4% higher than the next highest discipline of Materials Engineering, and 5% higher than Mineral Engineering, it suggests a very robust student culture and engagement. On the other hand, EngSoc elections have a 6% average turnout for its Officer elections, and both Electrical and Computer Engineering are at the bottom among the disciplines with a 7% and 9% average turnout, respectively. The results of my analysis, shown on the graph, is somewhat indicative of how lively a discipline is. Similarly, 2nd year elections have the highest turnout at an average of 29%; after that, it slowly decreases the longer students stay in the program. Board of Director elections have noticeably lower turnout than Discipline Club Chair elections, which may indicate students aren’t as clear on the responsibilities of directors, or have higher voter apathy. Discipline Club Chair elections, as expected, have a turnout that’s the average of the turnout of the 2nd, 3rd,4th year, and PEY rep elections.

Low voter turnout is a huge problem in any democratic institution because it questions the legitimacy of the election in the first place. Statistics, and the Central Limit Theorem, show that a sample can generally represent the wider population, but this is usually only true when the sample is unbiased and when there is a large enough sample. With some turnouts lower than 10%, it’s very hard to justify that these elections actually represent the will of the community, especially as the turnout rate might not be the same across different demographics in the engineering community. Chances are, the people who are already highly involved in EngSoc or other forms of student government are more likely to vote, but for the people who don’t vote or aren’t involved, they still have an equal say in the decision making process. While Chemical Engineering should be commended for their high turnout, is 34% really a number we should be aiming for? With 24% turnout for a school wide election at UBC, we can reasonably assume that their divisional elections’ turnout would be much higher than even Chemical Engineering. 34% means that around two-thirds of all Chemical Engineering students don’t have their voices heard, and this number grows to 94% for all engineering students with regards to who their EngSoc Officer is.

Low voter turnout has real life consequences too. In some elections, such as two EngSoc Officer elections, and the Board of Directors representative for Computer Engineering during the elections in March and April of 2019, the difference between the two candidates was a margin of less than 10%, and turnout was also below 10%. At this point, 1% of all eligible voters held the power to decide who wins the election. Can we be reasonably sure that the majority of the student body preferred the winning candidate as their representative, with such a razor thin margin, and a low voter turnout?

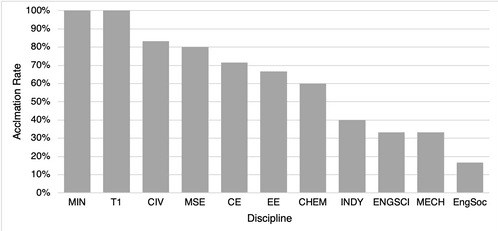

However, uncontested elections is an even greater problem. Four disciplines have rates higher than 80%: Mineral and TrackOne both had a rate of 100%, while Materials and Civil had rates of 80% and 83% respectfully. Roughly 57% of all EngSoc elections are uncontested. This means that voter apathy is so high that people aren’t even motivated to run. There is a mechanism to reopen nominations, which provides the voters another option in uncontested elections, but in my time at UofT, I’ve only seen it used once. Its use is rare, and about as meaningful as declining your ballot at federal elections. Representative democracy in general is all about giving the people the choice and the means to decide who represents them to make their voices heard, and when there is nobody to challenge another candidate in an election, or offer an alternative that reflects the diverse opinions of the student body, then the system is not performing the way it should. Whenever I think of acclaimed elections, I think of authoritarian regimes where they hold elections to seem legitimate, but only have one serious candidate running, who usually wins with an over 90% margin. I’m not saying that EngSoc elections are unfair or undemocratic, but it definitely creates the perception to some people that they might be.

After the 2015 federal election, Stephen Harper said something that I think any respected elected official, from Jagmeet Singh to Justin Trudeau, would agree with: the voter is always right. The low turnout, even compared to universities similar to UofT like UBC, as well as high uncontested election rates, are actually messages that the student body is sending to us. Either they don’t think student government is important, or they distrust student government, or they think that EngSoc and Discipline positions are a clique meant for only a certain type of people. Any of these three mindsets are bad for the community, and it brings up questions of how much legitimacy EngSoc and discipline clubs have. It may be easy to blame the voter, or focus our attention on more “get out the vote” efforts, but voter turnouts have been abnormally low for many years, and more and more elections are being uncontested every year. My opinion is that this is a serious problem that goes beyond the lack of voter awareness, and we should be devoting more of our attention to correcting the structural problems leading to low turnout and uncontested elections.