Ruknoon Dinder

Cannon Writer

This is a writing that reflects a part of me I don’t often express. I don’t particularly enjoy writing articles that pull at your heartstrings and I will admit I am not the best at them. If you are not one for emotional pleas, The Cannon always has far better articles that will satisfy your taste (pun intended). But if you’d like to hear a story about the upheaval that has gone through the Bengali culinary world over the past few months, grab a seat.

I guess all that is a really convoluted way of saying that I regularly watch Masterchef Australia (yeah, g’day mate, throw a sheila on the barbie and all that). This year, I noticed an interesting contestant on the stage of what is arguably the most famous cooking show in the world. Someone I had never seen before, yet someone who was about to touch the hearts of millions of Bangladeshis around the world. When I started this write up many words came into my mind and I was a bit confused about which words I would choose to describe unstoppable masterchef contestant Kishwar Chowdhury. She is an incredible cook, proud mother of two, graphic designer, and just a great soul. Kishwar’s father, a freedom fighter of Bangladesh, left the country fifty years ago to start a new chapter of his life in Australia. Though Kishwar was born and raised in Australia, Bangladesh still has a special place in her heart, a love she demonstrated at every stage of MasterChef through her cooking.

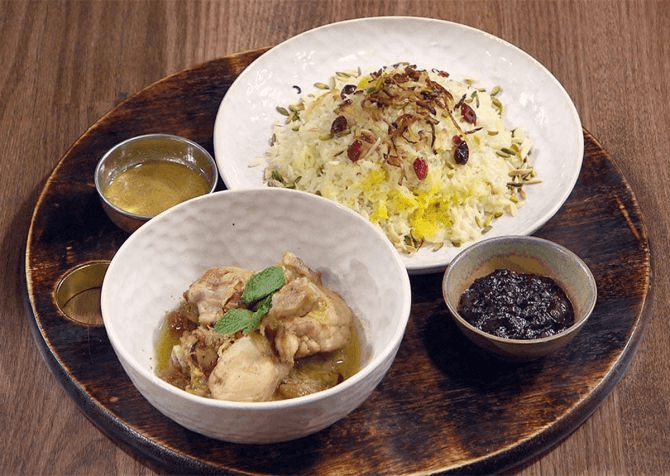

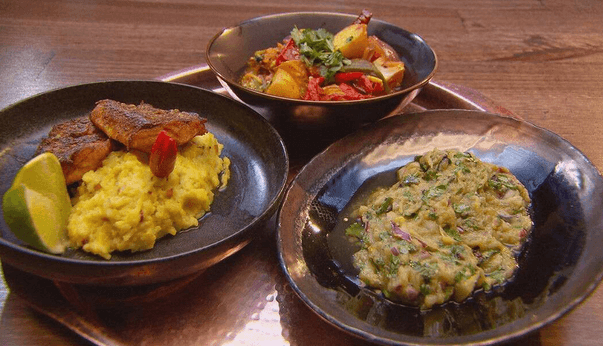

Correct me if I sound like a boomer, but I will claim that, until now, no one has felt the need to identify everyday Bangladeshi home-cooked food as a matter of prestige. If anything, the humble, day-to-day Bangladeshi dishes Khashir Rezala (Candied Mutton Curry), Shorshe Ilish (Hilsha in Mustard), and Begun Bhorta (Spiced Mashed Aubergine) were not considered special enough compared to the aristocracy of the lobster tails, barbecued ribs, or even potato salads. It was uncool to serve to other Bengali guests in the country, let alone be introduced to foreign tastebuds. Kishwar changed that. She strongly believed in the integrity of our unpretentious food, where the ingredients are few, and the cook does not hide behind flashy marketing.

When this season of MasterChef started and Kishwar was introduced, viewers in Bangladesh were naturally delighted. It’s great to see another Bengali on the global stage. But we have no shortage of those, from MPs in Canada, footballers in England, peacekeepers in South Africa, or doctors and engineers in Australia. It was certainly not a remarkable achievement back then. When she said she had a “small dream” of highlighting Bangladeshi food on the show, perhaps most of us took it casually. Obviously we have our share of famous Biryanis, and we wrongly assumed that that was the extent of her capabilities. However, as the season progressed, she demonstrated that she meant what she said. Starting from Machher jhol (Soupy Fish) to Jau bhaat (Rice Porridge), Lau chingri (Candied Shrimp with Gourd), to the inventive dessert highlighting Paan (Betel Nut Leaves), her trajectory has generated immense interest not just in her home country of Australia and her ancestral home of Bangladesh, but also in India.

Kishwar has given us the opportunity to treat our food like a cuisine. She has shown us the power of Bangladeshi cuisine. Soon after Masterchef Australia first aired, we invited a few of our neighbours to come try our food. The love and praise we got filled us with incredible pride for our ethnic cuisine, with our guests calling back and asking for recipes to create the exotic food enriched with bold flavours, explosive spices, and unapologetic sweetness. We never expected admiration of any sort and we were so very wrong at doubting such an essential part of who we were.

In a way, this article is as much for me as it is for you. What I truly want to recognise here is that Kishwar is just a medium. Bangladesh makes exponential levels of advancements every year. For a half a century old country, we’ve permeated every sector of the world – we’ve revolutionised agriculture, banking, education, and our garment sector as a global leader. Hell, we have world class athletes for a sport which should not even be associated with our country – golf. We dare on unimaginable levels. Yet when it comes to our culture, we’ve maintained the same level of secrecy and disdain we had when we hid our Bangalipona from the Pakistani rulers. We’re using half a century old cookbooks, geoblocked our clothing to Bangladesh, and abridged Hans Christian Andersen books for our children instead of passing down the stories of Nobabs and Rajkumars that we were told as children. We eat our food everyday, but never call it ours. We love our music, but never sing it out loud. This must change. A lady who is not even a Bangladeshi citizen showed us that it can change. How more blatantly can you make that statement than serving Pantaa bhaat, a meager food eaten by the subsistence farmers of Bangladesh, in front of the best chefs in the world?

But for now, we will focus back on our food. We will know the winner of Masterchef Australia by the time this article is published. But in my eyes, Kishwar is the winner. I believe it’s not just me; I think all Bangladeshis home and abroad would agree with me. She proved the phrase “Slow and steady wins the race” by her steadfast cooking in the entire Masterchef journey. Even though she cut her finger badly in Curtis Stone’s chicken testing, she didn’t give up cooking. She continued it and made herself safe with a mouth-watering dish. I would like to thank Kishwar, who has inspired us to dream big and who broke the barrier of austerity so that millions will now feel pride in sharing their culture with the world. She, who taught us how someone can be Australian, yet so authentically Bengali. She, who showed us that food can be served as a fabric with heritage, taste, and culture. She, who showed us that food isn’t just a bunch of ingredients; rather it is about memories and feelings. She is our inspiration, our hero, and she is the crown jewel of the history of Bengali food, as well as Bangladesh as a whole.

Every year, I write my F!rosh Week article for a certain subsect of SkuleTM. I know there are many Bangladeshis and Bengalis within SkuleTM, and within UofT, with many more coming next year. My final F!rosh Week article is for you. The progression of our culture is not up to the handful of filmmakers who make it into Cannes, or rare practitioners like Kishwar. It is on you. Don’t claim her success as your own to your mum; I know you’ll try to do it. Don’t keep sharing it on Instagram as a flex. Instead, build on it, and be another story. Don’t call your fuchkas pani puri anymore. You know the bloody difference. Explain it. Never apologise for being a Bangali. We survived a genocide and fought off nuclear powers to preserve Amar Sonar Bangla. It’s time we let it be known. To the rest of you, come try our food! I now know without doubt, you will come back wanting more.

*I would like to thank my friends from Dhaka University in Bangladesh and Deakin University in Australia who helped me research and fact check some of the sources I used. I am eternally grateful to you all.