Dilan Somanader

Cannon Senior Editor

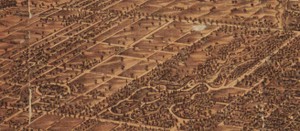

It was 1878, the year Edison patented his phonograph and Tchaikovsky composed his only violin concerto. And in Victorian-era Toronto—a city of muddy streets, gas lamps, and horse-drawn carriages—the School of Practical Science opened its doors for the very first time.

The idea of creating a professional school that could help Ontario keep up with the rapid pace of technological change was first put forth in 1871, by a two-man commission in the provincial government. The proposal was initially met with strong pushback from legislators, who were wary of the high cost (around $50,000) and potential redundancies with the University of Toronto (which already offered a two-year, albeit insufficiently rigorous civil engineering course). Nonetheless, a bill was eventually passed in 1873 to formally establish the school, with the goal of promoting the “development of the mineral and economic resources of the province.”

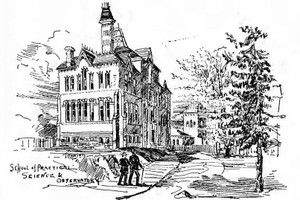

A small three-story, red-brick building, which would come to be known as the “Little Red School House”, was built on the University grounds in 1878. All that remained was to fill the crucial position of Chair of Engineering. In late June of 1878, the position was advertised in provincial newspapers and two scientific journals; nine men responded to the posting.

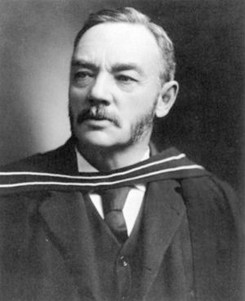

One of them was John Galbraith of Port Hope, Ontario, who was a graduate in honour Mathematics of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Toronto in 1868, and a recipient of both the gold medal in mathematics and the Prince of Wales Medal for overall proficiency. Following graduation, Galbraith held a number of engineering positions—from division engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railway, to mechanical draftsman for a company that manufactured machinery like steam engines and grain elevators. He later returned to the University to receive his Master of Arts in 1875.

Galbraith’s outstanding academic qualifications and ten years of extensive practical experience set him apart from the eight other applicants, and he was hired on September 28th, a few weeks after his 32nd birthday.

The First Term: Fall, 1878

In its earliest incarnation, the School offered a three-year program for a diploma that could be obtained in one of three departments: 1) Engineering, which included Civil, Mechanical, and Mining; 2) Assaying and Mining Geology; and 3) Analytical and Applied Chemistry. Courses for the engineering department were common among all three branches for the first two years, and in third year students would specialize in a branch of their choice.

The School served a dual purpose during its early years, as both a government-funded professional school and an extra building for the University of Toronto. Classes for the School of Practical Science took place on the second floor, which had a small private room, a library, a drafting room, and a lecture room that was shared with the University. The rest of the building was used by the University for courses ranging from mineralogy and geology, to biology and chemistry.

As the School’s only engineering professor, Galbraith was responsible for delivering all engineering courses. In addition to Galbraith, the faculty consisted of five other professors from the University: Prof. R. Ramsay Wright (Biology), Prof. H.H. Croft (Chemistry), Prof. E.J. Chapman (Mineralogy and Geology), Prof. J. Loudon (Mathematics and Natural Philosophy), and Prof. W.H. Ellis (Chemistry).

A sessional report submitted to Ontario’s Lieutenant Governor in December 1878 offers a glimpse into a school still in its infancy.

“The First Term of the present Session opened on the Third of October,” reports Prof. Wright, who was then-acting secretary of the School, “and although the fittings of the Building had hardly been completed, the Lectures and Courses of Practical Instruction were begun in most of the Departments.”

Seven full-time students entered that year, all of whom were enrolled in the engineering department. And of them, Wright says, “several have been previously engaged in practical Engineering work, and have entered the School with the object of gaining a more scientific and complete knowledge of their profession…” There were also several occasional students from the University, as well as from various medical and veterinary schools around the city, who were taking courses at the School in chemistry, biology, and mineralogy.

With the fall term wrapped up, Wright was happy to report that the terminal examinations had “indicated gratifying progress.”

Student Life

In the 1922 issue of the Transactions of the University of Toronto Engineering Society, several alumni and former faculty members from the “Old Red School” were asked to share their experiences. These are just a few of the many colourful anecdotes they told:

James L. Morris was the School’s very first graduate, having completed his diploma in Civil Engineering in 1881. He remembers the “October sports”, like steeplechase and walking races, held on the lawn in front of University College, and the Literary and Scientific Societies where one could listen to essays and speeches by the Arts students.

J.H. Kennedy (’82) recalls “the mischievous spirit of having fun with the Toronto police.” He recounts an incident when, after a school assembly, he and hundreds of other students from the University marched up Yonge to Bloor Street—singing college songs and tapping “heavy hickory canes” on the sidewalk. They eventually encountered the police and several students “were arrested upon their way home”, but “a collection was taken up the next day” and their fines were paid.

According to Prof. Loudon, the theatre was a “great attraction” for students; Friday nights and Saturday afternoons were often spent at the Grand Opera House for a Shakespearean play. One thing that stood out to Loudon during those early days of the School was the closeness between the students and teachers, who all “knew one another, not casually, but intimately.”

H.E.T. Haultain—a freshman in 1886 who later became a professor—remembers the school caretaker, “Prof.” Graham, who made drafting boards and sold them to students. “It was custom for the students to give him a Christmas present,” he writes, “and on one such occasion he was presented with a greased pig, which he was forced to pursue through the building for some time, much to the amusement of onlookers.”

For G.E. Silvester (’91), Halloween was an eventful night in the college year, when students would head to the theatre or take part in a “monster parade”. “The women’s residences were serenaded,” he recounts, “and the Toronto police force, which at the time was very inadequate, was given a rough evening.” Silvester recalls the stunts students would pull, like unharnessing horses from their carriages and chasing them away, or painting “unruly” freshmen with ink. He also remembers the boarding houses for students on McCaul, Church, and Henry Streets which charged $3 a week on average, as well as dining at the only students’ restaurant near College and Spadina.

T.R. Deacon (’91) remembers the boxing matches held every Friday evening underneath the Engineering Supply Room. “The whole school practically used to assemble,” he writes, “standing on benches around the wall, and watch us go to it until one went down.” The bonds between classmates were strong in those days: “…there existed a great spirit of camaraderie and one could borrow anything from a pipeful of tobacco to a dress shirt if anybody in the class had one.”

If there is one common thread running through each student’s experience, it is the love and adoration for Prof. Galbraith, or “Johnnie” as he was more fondly known. For T. Kennard Thomson (’86), Galbraith was “far and away the most outstanding feature of the Red School House.” E.W. Stern (’84) writes that beyond his outstanding technical qualifications, Galbraith was a kind and sympathetic man who took interest in each one of his students. “We, his old pupils, are his lifelong friends,” Stern says, “We owe him a debt which can never be repaid.”

An Ever-Evolving School

When the 1880s and 90s rolled around, Toronto was an expanding city in the throes of industrialization. Gas lamps were swapped out for electric lights; telephone poles sprouted along sidewalks; muddy streets were paved over with asphalt; and new buildings came up—among them, the Ontario Legislative Building in Queen’s Park.

The School of Practical Science underwent many of its own changes during the decades, including: the introduction of a degree program for Civil Engineering; the establishment of the Engineering Society; the creation of separate departments for Mechanical and Mining Engineering; and the addition of an optional fourth year to give students more time to perform hands-on laboratory work. The popularity of the School grew so rapidly with each passing year, that by the 1887-88 session, full-time enrollment had surpassed 50 students. But it soon became clear that the School was bursting at the seams by almost every measure.

In an 1887 sessional report submitted to the Minister of Education, Daniel Wilson (who was President of the University at the time) expressed deep concern at the growing lack of resources.

“With only one Professor of Engineering and a graduate assistant,” Wilson wrote, “it was found utterly impossible to institute complete systematic courses in Civil and Mechanical engineering and their subdivisions.” The burden on Galbraith was in fact far too great: by the 1883-84 session he was delivering lectures for a total of 14 engineering courses by himself, in addition to providing practical instruction in surveying and drafting.

The small size of the building was an urgent issue as well. Lectures had to be delivered in the drafting room for lack of space, “much to the inconvenience of other students engaged in drawing.” Without a proper meeting room, the Engineering Society was forced to store a large number of their periodicals in Prof. Galbraith’s office. And on top of being overcrowded, the building was neither properly ventilated nor well-lit; sanitation was poor; and an inadequate heating system caused water pipes to burst in the winter and flood rooms.

Additional lecturers were eventually hired to ease the burden on Galbraith, and the teaching staff grew steadily over the coming years. To remedy the lack of space, a large extension of the building which tripled the School’s area was completed in 1890. Engineering laboratories and testing facilities were also added to allow students to have experimental training with equipment like pumps, tanks, and turbines. The extension undoubtedly marked a turning point for the school. Local press became interested in the practical tests conducted at the labs on the quality of Canadian building materials, and it was not long before the Ontario government was finally satisfied that the School had been a good investment.

Throughout the 1890s and early 1900s Galbraith continued to work tirelessly to expand the School—pushing for the hiring of more staff and the installation of more equipment for the laboratories. As full-time enrollment surpassed 200 at the turn of the century and the issue of space was back on the front-burner, Galbraith concluded that the only solution would be a new building. The School submitted a student-signed petition to the Lieutenant Governor, which eventually led to the construction of the Mining Building. However, it would hardly be an end to the School’s accommodation woes: enrolment jumped to 475 by the time the building was completed in 1904, so it opened at capacity.

The conclusion of the 1905-06 session marked the end of the School of Practical Science. After 28 years in operation, it was finally incorporated into the University of Toronto as the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering. Galbraith became the Faculty’s first Dean, and remained devoted to his students until his death in the summer of 1914, aged 67. The “Little Red Schoolhouse” would be demolished in 1966 to make way for the Medical Sciences Building, but its legacy still reverberates to the present day.

To see how far our Faculty has come is both inspiring and humbling—from a small brick-building with seven students, to a world-renowned institution with nearly 8,000. And just as no one in 1878 could have imagined where we’d be now, there is no telling where we’ll be in 140 years. As the saying goes, you can never fully appreciate where you’re going until you know where you’ve come from.